invisible harms Harms OF MASKING iN THE LGBT+ COMMUNITY

The DATA

A Plos One study across a wide sample of 28 EU countries and an objective index of 197 countries found “that the majority (83.0%) of sexual minorities around the world conceal their sexual orientation from all or most people" (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019). This concealment in everyday life is called masking, and its necessity causes a variety of harms on the LGBT+ community. Because of sampling techniques, the authors of the study admit this may be an underestimate.

This project relies on this data and personal testimonies to discover these harms that masking causes. A range of harms are discussed, including mental, social, and physical. This data artifact aims to represent these invisible harms, bringing pain queer people feel everyday to the surface. The artifact also invites the user to experience these harms themselves metaphorically by putting it on.

This project begins where I often find myself on weekends: at a thrift store. After a long night of thinking about data physicalization, I knew I wanted to modify something instead of creating an artifact. Specifically, I wanted to modify a jacket because it relates to ideas about the closet.

I chose the modification route because I had a hard time thinking of objects to create from scratch, and I knew modifying an existing object would let me tailor its meaning more effectively. Because masking is hard to detect, I wanted to create something that would be the opposite. Clothing to me feels very similar to masking, and changing one's clothing is even a way people in the LGBT+ community practice this. The "mask" can be put on and taken off in different context, and so can a jacket.

The thrift store options you see here did not make the cut...

Luckily, I had a jacket in my closet for a long time that I'd never worn. Its thin material made it easy to embroider, and as a bonus I really enjoyed the recycling aspect of this project. I didn't have to buy a new object to modify, and I had most of the materials I needed already. The gray color of the jacket was going to contrast with colors I wanted to incorporate too.

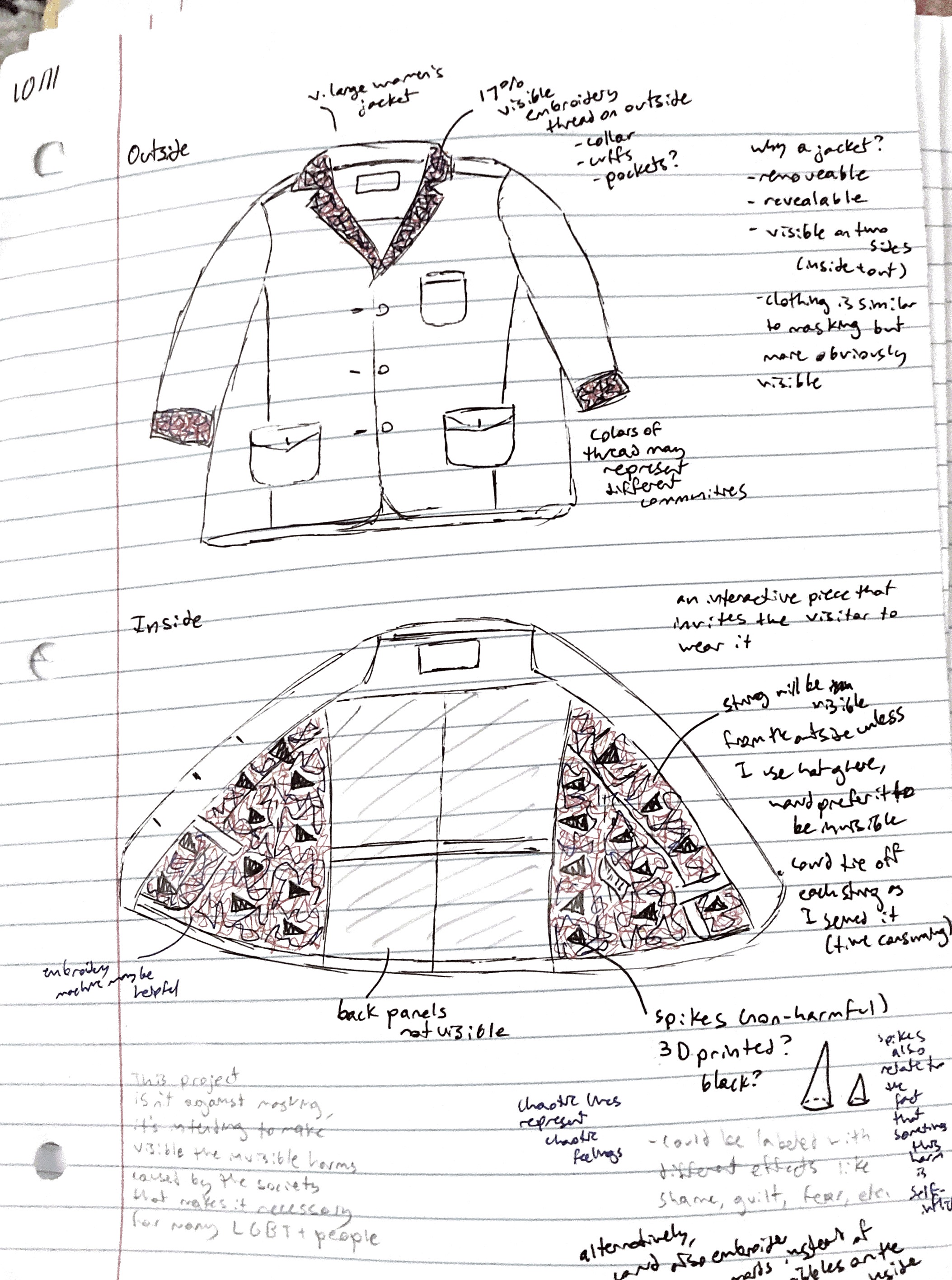

Pachankis & Bränström's estimate of the global closet—83% of LGBT+ people—can be reversed. In other words, 17% of the global LGBT+ community were not closeted in 2019. The following is a preliminary sketch where I thought about these two numbers.

I wanted to use both sides of the jacket (inside and out) to reflect these two statistics. I planned to flip down the collar and cuffs, showing a rainbow on 17% of the jacket from the outside. The cuffs were not embroidered in the finished design due to time constraints.

Don't ask why or how I came to own so much embroidery floss. I found the trove in a sewing kit, so I assume it was a hand-me-down from one of my relatives. In the stash I found six colors to my liking: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple. These colors bring to mind a rainbow and represent the LGBT+ community for the purposes of this project. I recognize not all members of the community identify with this color palette, but one must decide on some color scheme to move forward.

The second component of this project involved invisible harms. I needed a way to make them visible and in conversation with the wearer. I didn't want the jacket to be literally harmful, so I decided to 3D print spikes and smooth them for a merely uncomfortable effect instead.

Putting on a "mask" or jacket that harms the wearer also speaks to the fact that sometimes harms can feel self-inflicted and personal. The spikes are not visible from the outside of the jacket. Harms can only be shared via selective sharing, and in this project's case: visibility.

The image to the right is a test tray of spikes I made using Tinkercad. After they were printed, I chose the largest spike and one of the medium spikes to duplicate for the lining of the jacket.

THE HARMS

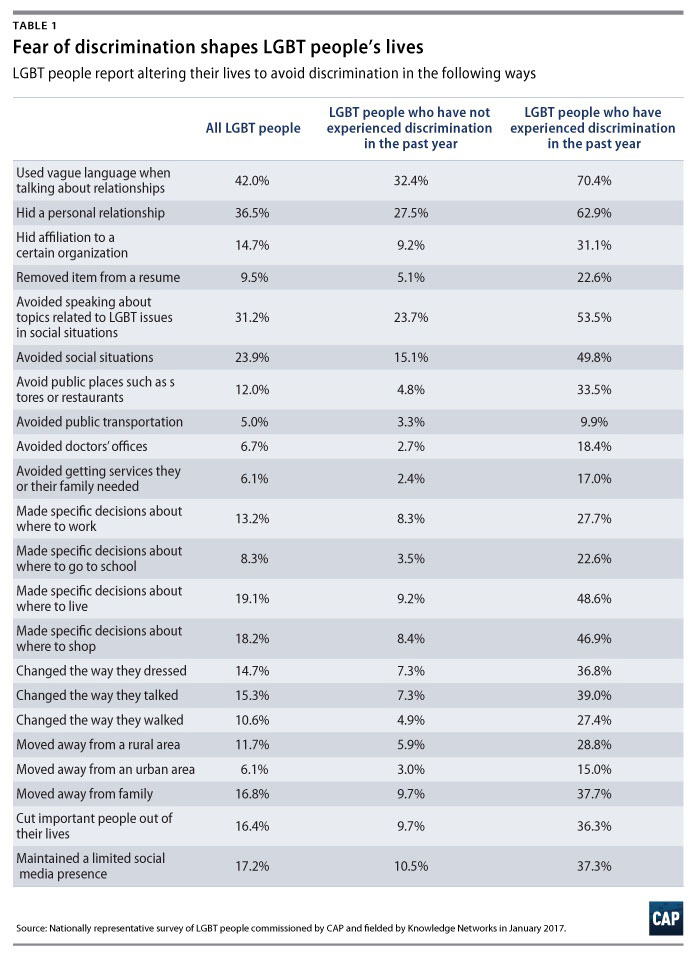

What are these invisble harms? There are many harms caused by masking in the LGBT+ community, and they impact all areas of life. A survey in 2017 found that "LGBT people hide personal relationships, delay health care, change the way they dress, and take other steps to alter their lives because they could be discriminated against" (Singh & Durso, 2017).

Examples

- Mental Harms: Anxiety, Depression, Loss of Identity

- Emotional Harms: Loneliness, Fear, Guilt, Shame, Unhappiness

- Social Harms: Hiding Relationship Status, Partner Erasure, Distancing from Social Events, Silencing PDA, Moving

- Physical Harms: Stress, Anxiety, Fatigue

It is very difficult to measure harms qualitatively when they exhibit wide variations and tend to be personal. Every LGBT+ person will have a different set of harms they deal with by masking. Some feel no harms, while others "pass" and may only feel an internal feeling of discomfort. Others choose to stifle their identities in bigger ways and face more harms. For this reason, I decided to rely on personal testimonies through blog posts and forums to inform us of the types of harms masking causes. The following are three personal testimonies.

Personal Testimonies

"On a day to day basis I have to make the decision of whether or not to out myself, whether to hide or whether to reveal; to the builders coming to fit the new bathroom as I explain the house belongs to my partner (who is a she not he), to the doctor who has presumed my partner is male and is asking me what birth control I'm on, to the child in the drama class I teach that's just asked if I have a husband. If I lie, or lie by omission - if I skirt around mentioning my partner or my sexuality, I usually find I immediately feel guilty" (Taylor, 2021).

"I wanted to be myself, but I hoped and prayed that my feelings would go away, because I feared rejection. Growing up I didn’t have the language to tell people I was bi. I knew I wasn’t only attracted to men but felt ashamed and had to hide it from my friends. At school, calling someone a lesbian was considered the worst insult, so I knew that if I came out, I’d risk losing people or being treated differently. That made me push down my feelings and hide parts of myself, even from myself" (Maher, 2020).

On hiding transgender identity: "I am always questioning my own perception of reality" (Anonymous via Kaplan, 2013).

After a few hours of sewing and needle stabs, I embroidered the collar all the way around the jacket. To get the coverage right, I wore the jacket and pinned where I wanted the embroidery to stop (pictured left).

Now, how about the inside?

I realized during the design phase that I couldn't directly embroider the inside of the jacket or else the threads would show through on the front as well. Because this defeated the purpose of the project, I decided to cut panels of another fabric, embroider them, and attach them to the inside of the jacket.

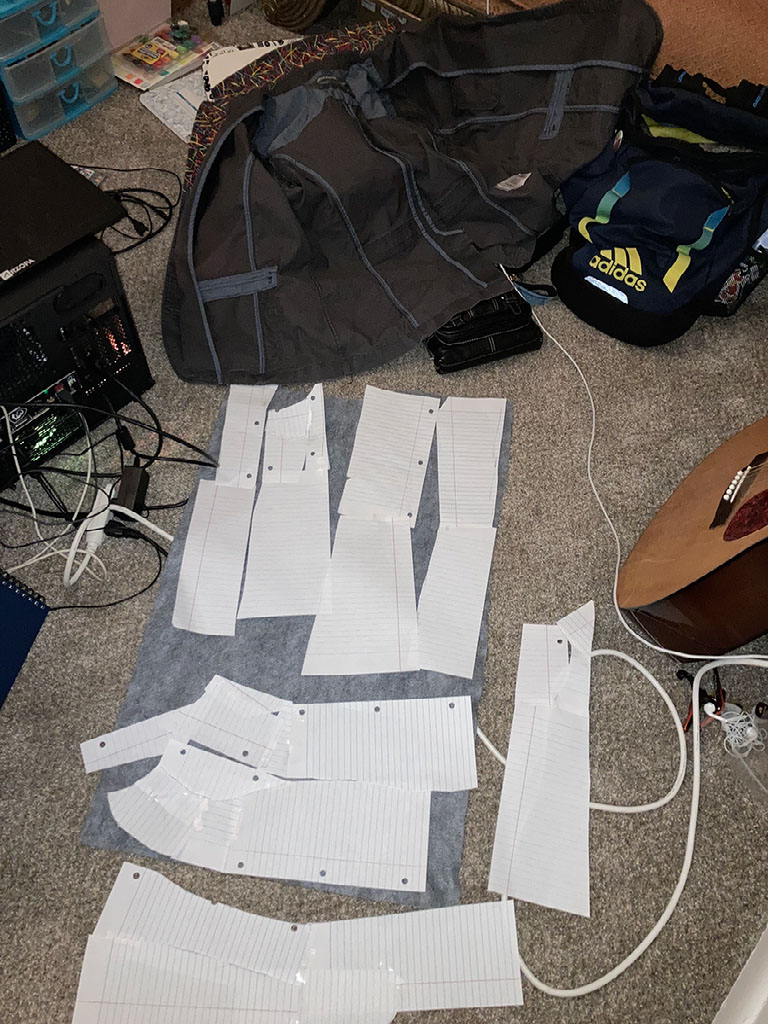

The first fabric I chose was gray felt (below), and was too small. Luckily on my next visit to the makerspace I was able to borrow some gray fabric for my project (right). I returned the extra fabric to the makerspace.

I stretched the fabric taut and traced the nine inside panels with notebook paper. These made for pretty good mockups.

I ambitiously started the inside of the jacket by stitching one side of the first panel into the jacket using very small stitches. Then I embroidered the panel with the six colors. I always started with red and ended with purple, and this methodical practice gave me a lot of time to reflect during this project. Was this project indirectly harming LGBT+ people, implying that masking was a thing they shouldn't do?

This conflict is reflected in Pachankis & Bränström's study. According to the authors, masking is a double-edged sword. It may keep one safe, but it also dampens visibility of minority communities as a whole, which reduces the perceived footprint and need for social change (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019).

Grappling with this reality, I finished one panel, stitched it in place with thread and tried on the jacket. The gray stitches were nearly invisible! This was great, however there was still one problem.

It looked a mess.

Unlike the jacket, a panel had no strength to it and it puckered even though I tried to keep my stitches loose. Without a sewing machine to properly sew the panels to the jacket and keep tension, I needed to find another way.

TO GLUE OR NOT TO GLUE?

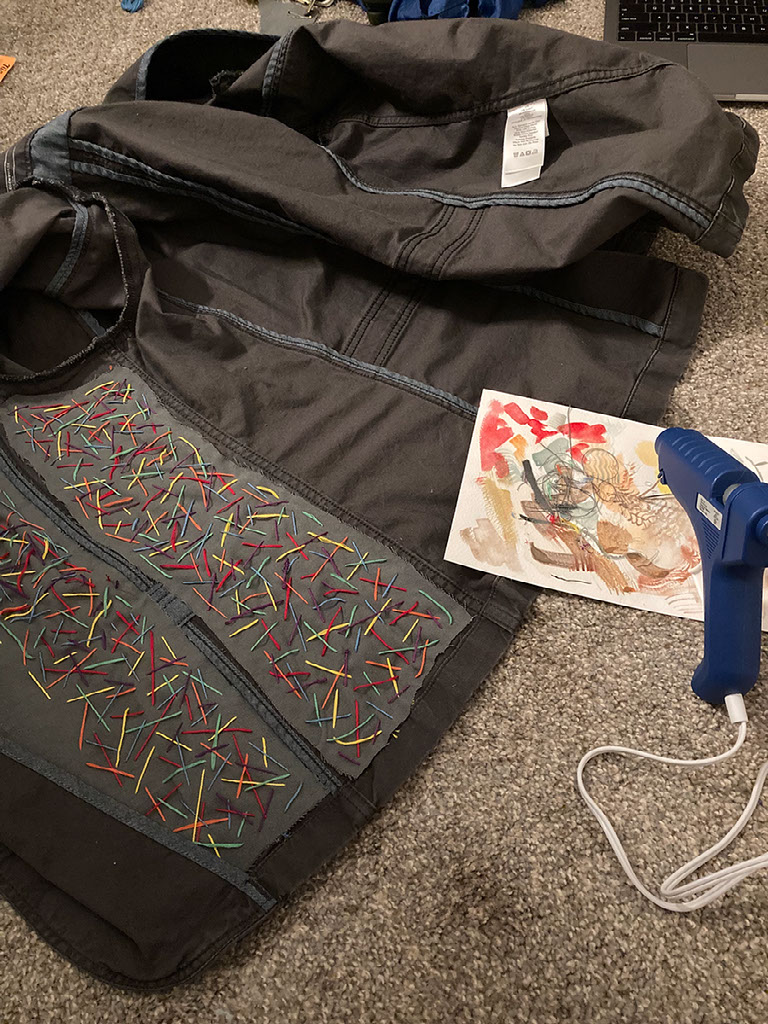

Spoiler in image above: I bought a hot glue gun.

Knowing that hot glue is a temporary bonder, I bought Gorilla Glue sticks and crossed my fingers. Hot glue did have the advantages of letting me keep tension (less lumpy fabric!) and sped up the attaching process. Speed was especially valuable, since each panel took about 1.5 hours to embroider with all six colors—excluding panel 5, a tiny 6 inch piece between panels. Before attaching I cleaned up the edges with scissors. Each finished panel took about 15 minutes to hot glue to the jacket.

Embroidery complete!

With the panels complete, let us go back in time to check on the 3D prints.

The Spike Saga

The prototypes printed well. I chose the brim option when they were printing so I would have minimal clean up to do. Once the test tray printed, I cleaned the eleven spikes and judged which sizes I wanted to use on the inside of the jacket

As I mentioned earlier, I chose a medium-sized spike and the largest to reprint for my project. The different sizes reflect that some harms can be more painful than others. This varies by personal experience.

Now it was time to print and print and print spikes to go all over the inside of the jacket! This, dear reader, is where the plan unraveled.

This data physicalization project was started well before fall break at my university, and I sent my trays to the printer with blind optimism, thinking they would print before commencement, or at least print over the break.

I was wrong.

I was misinformed about how to use the 3D printing queue in the makerspaces at my university. What I thought was a backlog in the system was actually an infinite holding cell for my prints. I realized this after fall break and properly sent my prints to a machine.

Spikes gathered, I now had to de-brim and sand them, plus cover that shade of blue. The brims came off easily with brute force and scissors, and I smoothed out the spikes with sandpaper like before. To start the adhesion process, I arranged the spikes how I wanted on the jacket and took a photo for reference.

Then it was time to paint them black. While aesthetically pleasing, a calming blue didn't carry the metaphorical weight I wanted. I purchased black craft paint and painted the spikes. The spikes were attached to the jacket using a stronger adhesive (not hot glue).

RECOMMENDATIONS

How can libraries and makerspaces respond to harms caused by masking in LGBT+ communities? From my perspective, when people enter one of these spaces, they do not want to be confronted with their identities. They want to feel normal, so fostering spaces of respect, inclusion, and community are the best way forward. It is not the individual who needs to "unmask" themselves, but society who needs a new face and perspective towards the LGBT+ community. Makerspaces and libraries have historically been places of radical change, and being supportive places for masking individuals is just one way they can respond to these invisible harms and support discriminated individuals.

- Create inviting, inclusive spaces with signage, policies, and staff training

- Support those who are "out" in a positive manner

- Allow those who wish to remain closeted do so, and do not ask for personal information

Resources

Pachankis, J. E., & Bränström, R. (2019). How many sexual minorities are hidden? Projecting the size of the global closet with implications for policy and public health. PloS One, 14(6), e0218084. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218084

Singh, S., & Durso, L. E. (2017, May 2). Widespread discrimination continues to shape LGBT people’s lives in both subtle and significant ways. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/widespread-discrimination-continues-shape-lgbt-peoples-lives-subtle-significant-ways/

Taylor, A. (2021). Hiding your identity takes its toll. Diversityrolemodels.org. https://www.diversityrolemodels.org/news/hiding-your-identity-takes-its-toll

Maher, M. (2020, February 6). How hiding my bi identity affected my mental health. Stonewall. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/about-us/news/how-hiding-my-bi-identity-affected-my-mental-health

Kaplan, Ami B. Hiding – Discussions of Mental Health Issues for Gender Variant and Transgender Individuals, Friends and Family. Transgender Mental Health, 9/2013, https://tgmentalhealth.com/tag/hiding/.